Neural Distance Embeddings for Biological Sequences 🧬

The recent paper ‘Neural distance embeddings for biological sequences’ by Corso et al. introduces NeuroSEED, a promising new technique for learning representations of biological sequences. The authors boast fast and accurate heuristics for inference on phylogenetically-related sequences such as edit distance approximation and hierarchical clustering.

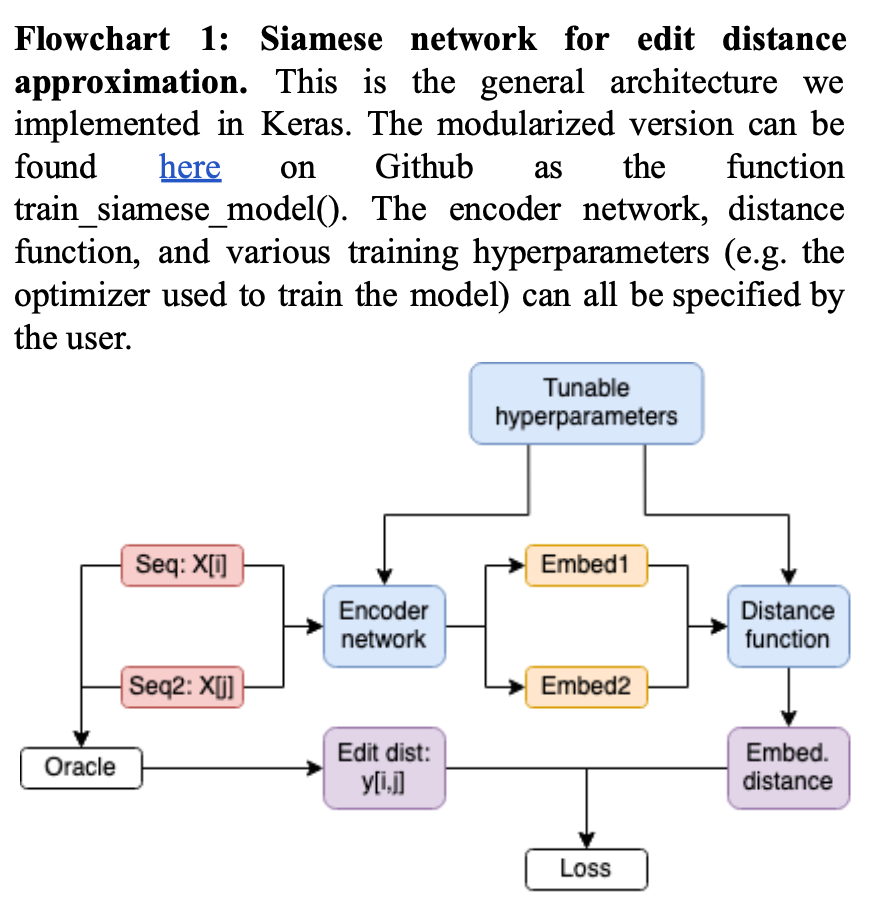

The main idea of NeuroSEED is to create a Siamese neural network which encodes any two sequences in a dataset so that their distance in embedding space (according to some distance metric chosen by the user) is as close as possible to the true distance (obtained by e.g. computing edit distances directly). While promising, the authors’ results were quite preliminary. Two limitations in particular stand out in their analysis.

First, although they tested their method on three datasets, all datasets were produced from different regions from the 16S rRNA gene, which is known to have very strong structural constraints. Since the value of these learned representations depends on the strength of the underlying manifold (unsurprisingly, this approach fails to compress randomly generated strings of DNA), the stronger-than-normal constraints on 16S rRNA sequence may translate into non-generalizable results. Thus, one of the goals of this project was to investigate the ability of this approach to generalize to other sequences. We successfully ran the NeuroSEED algorithm on a set of 7,010 sequences of the PheS (phenylalanine-tRNA synthetase, subchain A) gene. Because of computational and time constraints, we did not explore in silico mutation trees or noncoding DNA.

The second limitation of the original paper is the authors’ approach to test-train independence. Although there is no commonly agreed-upon approach to train-test independence in a phylogenetic context—indeed, the authors’ approach of choosing samples randomly without paying special attention to the relationship between samples is common—it becomes difficult to disentangle desirable forms of overfitting (manifold learning) from undesirable overfitting (e.g. by memorizing distances between pairs of neighbors in the training set). The original datasets used by the authors are densely sampled, and thus it is quite likely that, for any pair of sequences in the test set, the training set contains pairs of very closely related sequences with known edit distance.

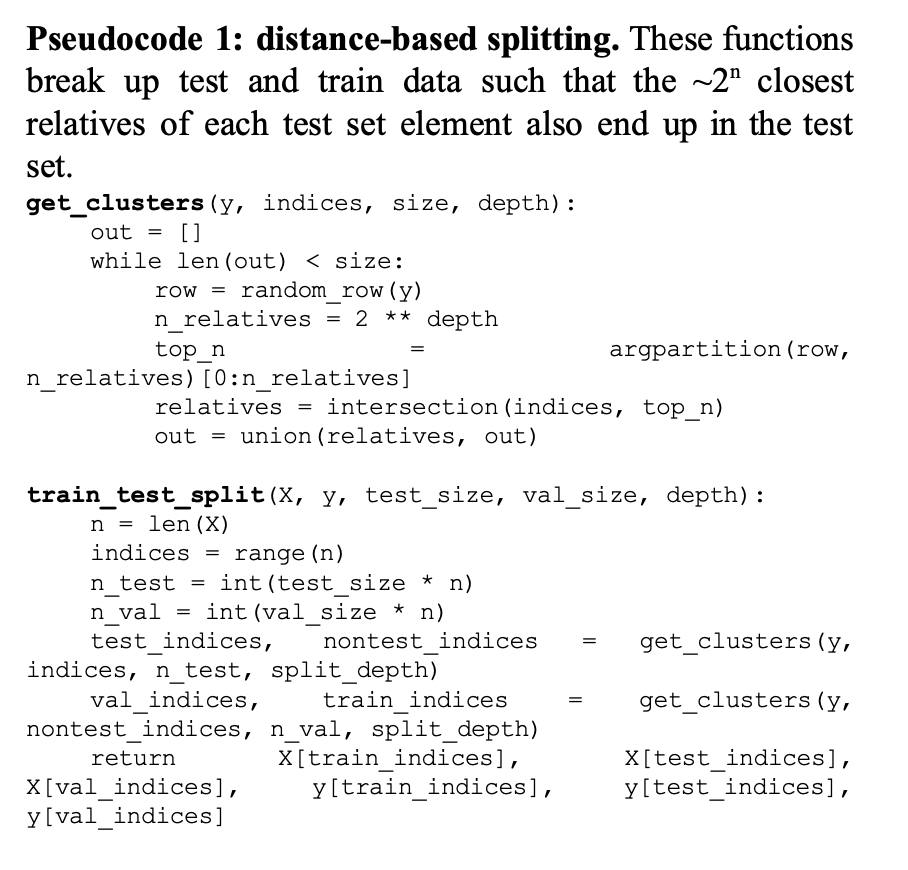

To explore this, we introduced a “phylogenetic” approach to train-test split, where entire subtrees of height n are added to the test set. This ensures that the model cannot memorize relationships between closely related sequences, and instead must rely on deeper underlying structure in the data. We expected that the more the model tended to memorize specific distances, the worse the gap between training and test loss would be as n increased. We ran this on the same set of 7,010 PheS sequences for values of n from 1 (random) to 8 (test set consists of subtrees of ~256 genomes). Because of memory and time constraints, we did not repeat this analysis on the 16S rRNA dataset. Additionally, we experimented with different model architectures, hyperparameters and distance functions to determine the most effective way to embed sequences quickly and at scale.

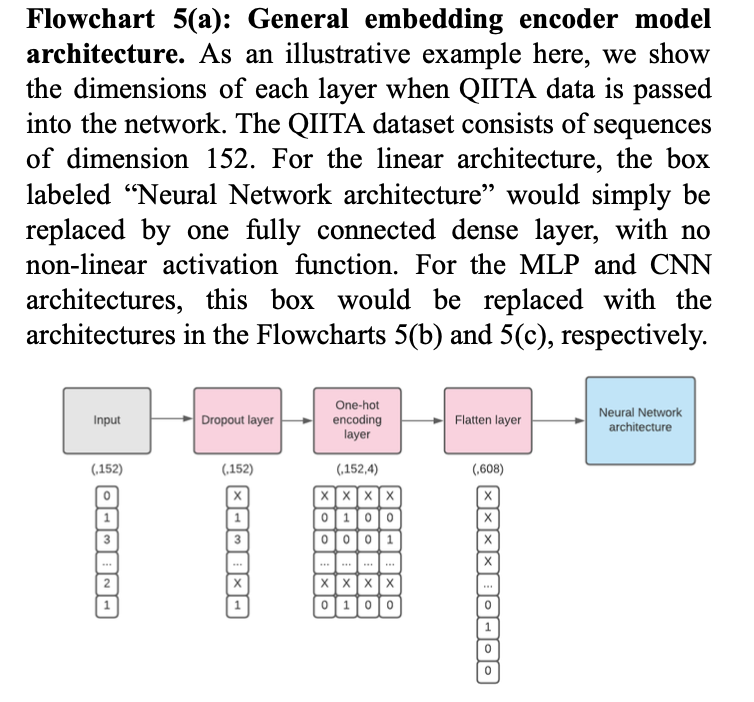

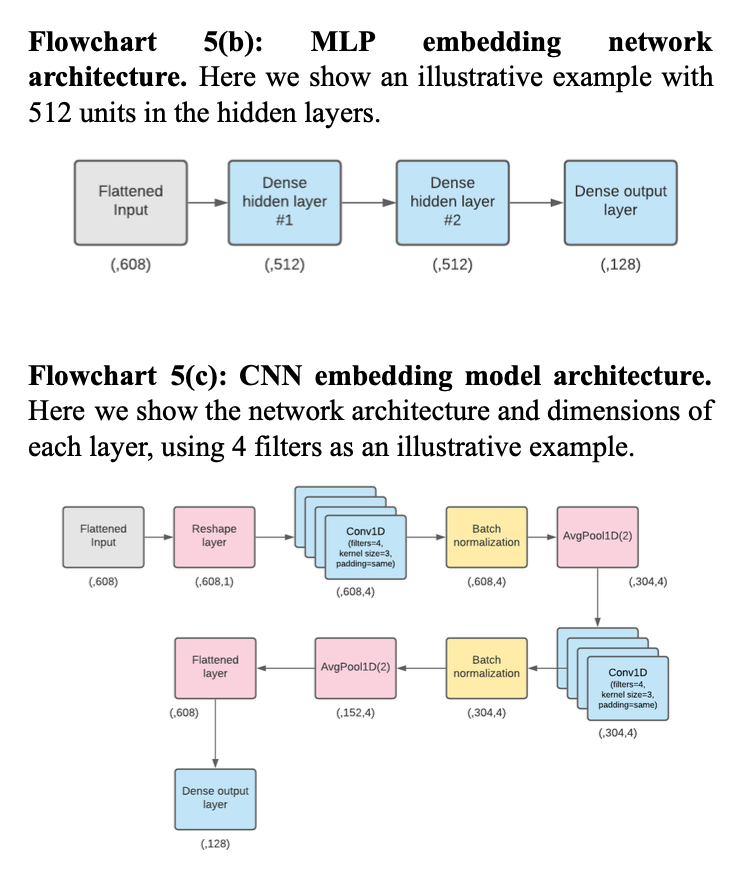

In terms of model architectures, we attempted to replicate three types of embedding models mentioned in the paper, in order to determine which architecture performed best: (i) the linear embedding model, which was made up of one fully connected layer without any non-linear activation function, (ii) the MLP model, which was made up of two fully connected hidden layers with non-linear activation functions and one fully connected output layer, and (iii) the CNN model, which was made up of two one-dimensional convolutional layers with batch normalization and average pooling after each. Within each model architecture studied, we included a dropout layer immediately following the input layer.

For each model architecture, we also performed hyperparameter tuning across the following model hyperparameters: (i) dropout rate, which was tested across all model architectures; (ii) choice of activation function, which only applied to the MLP and CNN architectures; (iii) number of units in the hidden layers of the MLP; and (iv) number of filters used in the convolutional layers of the CNN model, as well as various training hyperparmeters, such as batch size and learning rate, in order to evaluate which hyperparameter selections led to the greatest efficiency, in terms of both performance–i.e. loss minimization–and training speeds.

We also evaluated all of the distance functions studied in the paper for each of the model architectures described above. This essentially amounted to an investigation of different loss functions, as we defined mean squared error using the selected distance metric as our loss.